| |

|

Award Topics

"Re-aligning Values in a Transforming World Order: What needs preserving, reevaluating, and redefining?"

The theme of the 2025 Sakıp Sabancı International Research Awards was "Re-aligning Values in a Transforming World Order: What needs preserving, reevaluating, and redefining?"

The Special Jury Prize, presented as part of the 2025 Sakıp Sabancı

International Research Awards, was awarded to Wendy Brown, a UPS Foundation Professor at the Institute for Advanced Study, academic, political theorist, and social theorist.

Wendy Brown, a highly influential political and social theorist who offers a powerful critique of changing values in an era of globalization, neoliberalism, and democratic decline, is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley. Her academic interests include the history of political theory, feminist theory, contemporary critical legal theory, 19th- and 20th-century Continental philosophy, and contemporary American political culture. Her work has been translated into over twenty languages. She has lectured worldwide and has held numerous prestigious fellowships and visiting professorships. She has recently served as visiting professor at Columbia University, Cornell University, Birkbeck College, University of London, and the London School of Economics.

THE ESSAY WINNERS

Uğur Aytaç, Department of Philosophy & Religious Studies, Utrecht University

“What is the Point of Social Media? Aligning Corporate Purpose with Democratic Values”

Cenk Özbay, Sabancı University, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

“When Values Skirmish. Religion, Sexuality, and the End of ‘Mutual Exclusion’ in Turkey’s Backsliding Democracy”

Vafa Ghazavi, University of Sydney / School of Social and Political Sciences

“Restless Freedom in a Broken World”

JURY

The jury, chaired by Sabancı University Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences faculty member Ayşe Betül Çelik, included Sabancı University Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Dean Prof. Dr. Meltem Müftüler-Baç, Sabancı University Board of Trustees member Melisa Sabancı Tapan, Laurier Political Science Department faculty member Prof. Kim Rygiel, SOAS University of London International Relations Professor Fiona Adamson, University College London Faculty Member Prof. Sir Geoff Mulgan, and Lund University Political Science Professor Karin Aggestam.

|

| |

|

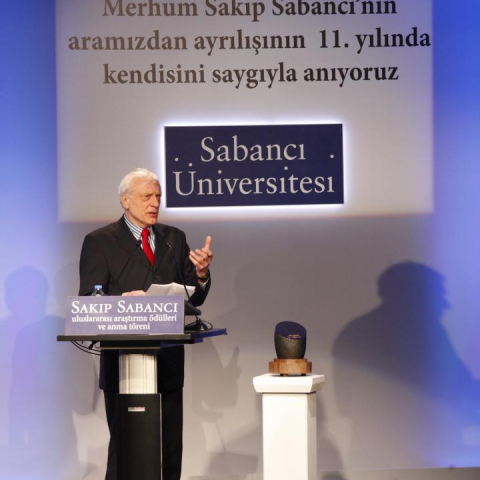

The late Sakıp Sabancı, Honorary Chair of Sabancı University, was commemorated with a special ceremony on the 20th anniversary of his passing. As part of the "Sakıp Sabancı International Research Awards and 20th Anniversary Commemoration Ceremony" held at the Sabancı Center, a panel discussion entitled "Sakıp Sabancı's Vision: Navigating the Future in Our Globalizing World: Trends, Risks, and Opportunities" was held. The panel featured prominent scientists from Turkey and around the world, as well as academics who have received the special jury prize in previous years.Another important item on the agenda of the 20th Anniversary Special Commemoration Ceremony was an artificial intelligence model that aimed to pass on the vision and values of the late Sakıp Sabancı to future generations. As part of the project, Sakıp Sabancı's speeches, writings, audio recordings, and images were processed using large language models and specialized algorithms. This meticulous work resulted in the development of a digital model that simulates Sakıp Sabancı's mind and way of thinking as realistically as possible under today's conditions. This AI model was used at the Sakıp Sabancı International Research Awards and the 20th Anniversary Commemoration Ceremony. At the ceremony, Sabancı University Board of Trustees Member Melisa Sabancı Tapan held a live conversation with Sakıp Sabancı's AI model. The project has been recognized with numerous national and international awards.

|

| |

|

Award TopicsThe Sakıp Sabancı International Research Awards, which have been held for 18 years following the will of Sabancı University Honorary President Sakıp Sabancı, rewarded young researchers and a scientist who have made significant contributions to academic studies in the field of republicanism within the scope of this year's theme, "The 100th Anniversary of the Republic of Türkiye: Republicanism in Theory and Application".

At the Sakıp Sabancı International Research Awards and Commemoration Ceremony, the Special Jury Prize was awarded to Philip Pettit, the L.S. Rockefeller Professor of Human Values at Princeton University since 2002 and Professor of Philosophy at the Australian National Universitysince 2012.

THE ESSAY WINNERS

Dolunay Bulut,The New School for Social Research / Politics

“Republic after New Authoritarianism: Constitution as an Object of Fetish”

Burak Tan, University of Chicago, Department of Political Science

“The Dual Challenge of the Anatolian Revolution: Anti-Imperialist Self-Determination as Identity and Critique”

Banu Turnaoğlu Açan, Sabancı University

“Republicanism in Turkey: Visions, Dreams and Cultivations of a Political Reality”

APPLICATIONS ASSESSED BY AN INTERNATIONAL INDEPENDENT JURY

The evaluation of the applications submitted in the award program, which is led by the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences and the Istanbul Policy Center of Sabancı University, is carried out by an independent and international jury. Within the scope of the award program, a different theme is determined every year from all fields of social sciences, from economics to politics, history, and psychology.

|

| |

|

Award Topics“The Future of Globalization: Return of the State?” The 2022 theme of the Sakıp Sabancı International Research Awards was “The Future of Globalization: Return of the State?”. Professor Pippa Norris, who has taught at Harvard for three decades as the Paul F. McGuire Lecturer in Comparative Politics, has been found deserving of the Jury Prize. The author of 50 books about government systems, electoral integrity, and democracy, and the scientist with the second highest number of citations in the field of social sciences according to Google Scholar, Professor Norris is also the Founding Director of the Electoral Integrity Project implemented by Harvard University and the University of Sydney. WinnersUfuk Akçiğit (USA - Chicago University) & Sina Ateş (USA - Federal Reserve Board - The views in this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or of any other person associated with the Federal Reserve System-) Mert Moral (Turkey - Sabancı University) & Evgeny A. Sedashov (Russia - National Research University Higher School of Economics) Paula D. Ganga (USA - Columbia University) JuryDr. Oya Yeğen, Faculty Member of Sabancı University Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, was the chair of the jury, and the other members of the jury were Prof. Dr. Fuat Keyman, Sabancı University Vice President and Director of the Istanbul Policy Center, Prof. Dr. Meltem Müftüler-Baç, Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Sabancı University, Prof. Dr. Houchang Chehabi, Professor of International Relations at Boston University, Prof. Dr. Sheri Berman, Professor of Political Science at Columbia University, Dr. Mustafa Kutlay, senior lecturer in the Department of International Politics at City, University of London, and Dr. Kerim Can Kavaklı, assistant professor of political science at Bocconi University. Winning Articles

Economic Policy and the Role of Government in a Globalized World

The Reversal of Electoral Fortunes: Anti-Elitist Attitudes in the Age of Populism and Globalization

Bringing the State Back In: Populism, Economic Nationalism and the Instrumentalization of Globalization in Europe Keynote SpeechesProfessor Pippa Norris, winner of the Jury Prize at the 2022 International Research Awards, said, “I am truly honored and delighted to be able to participate in this year’s Sakıp Sabancı International Research Awards, one of the foremost world prizes in terms of recognizing and encouraging excellence in the social sciences.”. In her speech, Norris, referring to the theme of the 2022 awards, said, “Globalization is a global phenomenon and it is complex. It should not be confused simply with Westernization, nor with Americanization, an older concept, as the word is sometimes called. Many of those who are leading global countries are in fact those in Europe, like the Netherlands, like Belgium, like Singapore in Asia, highly-integrated with world economies, as the United States is as well. Turkey currently ranks about 58th out of 208 independent states in the 2021 KOF globalization index. And many values are changing in countries around the world.”

|

| |

|

Award Topics"Post-Corona World And Turkey: Social Psychological And Political Impacts Of The Pandemics.” In coping with Covid-19 pandemic, government policies in the world displayed considerable differences. While some governments implemented social distancing through emergency laws, others approached this as a matter of personal choice and ventured into persuading their citizens towards self-confinement, with mixed success. In the fight against the pandemic, the success of the government policies became increasingly dependent on the behavior of their citizens. Civic activism was curtailed along with the decline in the citizens’ ability to come together, organize and advocate. Nevertheless, new civil society actors and a novel type of civic activism emerged in attempts to provide essential services such as food and masks, stop the spread of incorrect and harmful information as well as protect the disadvantaged and marginalized groups. What were the social psychological factors in understanding the impact of perceived threat of spreading Covid-19? Did the pandemic increase potentially maladaptive collective defensive behaviors, such as stigmatization, xenophobia, social isolation, fear of job loss, distrust toward health system and governments, as well as adaptive social behaviors, such as, social cohesion, creative collective actions, and altruism? What were the factors behind the adoption of such different government policies and citizen behavior in the face of the pandemic? Did the pandemic trigger novel government policies and citizen behavior or rather lend more credence to the already existing tendencies and status quo? What were the impacts of societal underpinnings such as the prevalence of individual and/or collective life styles in different societies in addressing the pandemic? Can individual autonomy coexist alongside the collective needs of the societies facing the pandemic? How did the government and citizens in Turkey respond to the pandemic and how do these responses compare with their counterparts in other countries? Can responses to the pandemic enable us to cope better with other impending threats such as climate change? WinnersEssay Award Winners:

Associate Professor Ayşenur Dal and Associate Professor Efe Tokdemir, both from Bilkent University

Onurcan Yılmaz From Kadir Has University and Ozan İşler from Queensland University of Technology (Australia)

Sinan Alper from Yaşar University Winner of the Special Jury Award: Professor Susan Michie JuryChair of the Jury Professor Nebi Sümer, Faculty Member of Sabancı University Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

Professor Fuat Keyman, Sabancı University Vice President and Director of the Istanbul Policy Center

Professor Meltem Müftüler-Baç, Dean of Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Sabancı University

Professor Adil Sarıbay, Faculty Member at Kadir Has University

Professor Ayşe Üskül of the University of Kent, Kevin N. Ochsner, Chair of Psychology at Columbia University

Associate Professor Jay Van Bavel, New York University. Winning Articles“Socio-psychological dynamics in the fight against Covid-19 in societies with underlying conditions” by Associate Professor Ayşenur Dal and Associate Professor Efe Tokdemir, both from Bilkent University

“Cognitive and behavioural consequences of the Covid-19 threat around the world and in Turkey” by Onurcan Yılmaz From Kadir Has University and Ozan İşler from Queensland University of Technology (Australia)

“Believing Covid-19 conspiracy theories: Not a bug, but a feature of human nature” by Sinan Alper from Yaşar University Keynote SpeechesWinner of the Special Jury Prize, Professor Susan Michie, behavioral health scientist, also known as a political activist in the field of public health, delivered an address at the award ceremony. Saying that she was extremely honored to have been awarded the prize, Professor Michie continued, “I would like to share with you how psychology helps to fight Covid-19. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, governments all over the world have asked people to change their behaviors. We have acquired new habits such as keeping social distance, wearing facemasks, self-isolating. However, observance of the rules depends on capability, opportunity and motivation. These 3 elements directly impact behaviors. Psychologists have played a key role in understanding and changing behavior to tackle Covid-19.” Pointing out that, “if we want to change the behaviors of citizens, we may want to achieve this by changing the behaviors of others; health professionals, employers, policy-makers and politicians,” Susan Michie added, “First of all, we should ensure that policy-makers change their behaviors. The first step to ensuring change is to make recommendations for behavior change. Our research group has identified 93 behavior change techniques. Which techniques we use will depend on what will be appropriate for different populations, different settings, and different behaviors. So, if our task was to increase self-isolation, we would not use techniques to increase motivation such as threatening people with large fines, but instead use techniques aimed at increasing opportunity, providing social, financial, and practical resources to support self-isolation. In this context, trusted leadership is important. Communication must be honest, open, clear and transparent. And telling people not only what to do but explaining why people need to adopt certain behaviors; giving them a rationale. It is necessary to know and listen to the communities, and include them in decision-making. Governments don’t always do what we advise but we always try to ensure the best advice. I hope that the government in Turkey is also benefitting from the advice of psychologists and other behavioral scientists in tackling Covid-19. No person, and no government, can protect itself on its own. Humans are all interconnected, and solutions must be global. We can only protect ourselves by protecting each other.”

|

| |

|

Award Topics“Economics and the Future of Turkey”

One of the most striking results in the modern economic theory is to show that markets are often imperfect. In such cases, wisely designed economic policies can increase efficiency and decrease inequality. At its 15th year, the Sakip Sabanci International Research Award will acknowledge studies concentrating on the government’s role in and economic policies related to the wide range of topics from inequality to income distribution, climate change to energy, traffic congestion to air pollution, transportation to housing. The studies must be contributing to the economics literature at the universal level as well as generating ideas that can in principle benefit Turkey. WinnersWinners of the Research Awards:

● Jonathan D. Hall, University of Toronto “Can Tolling Help Everyone? Estimating Aggregate and Distributional Consequences of Congestion Pricing”,

● Hans Koster, Vrije University, Amsterdam “The Welfare Effects of Greenbelt Policy: Evidence from England”, and

● Nick Tsivanidis Berkeley University, California “Evaluating the Impact of Urban Transit Infrastructure: Evidence from Bogotá’s TransMilenio”.

Winner of the Special Jury Award: Professor Lord Nicholas Stern JuryEren İnci, Sabancı University - President of the Jury

Fuat Keyman, Sabancı University - Istanbul Policy Center

Özgür Kıbrıs, Sabancı University

Kemal Derviş, Brookings Institute

Professor Gilles Duranton, University of Pennsylvania

Professor Robin Lindsey, UBC Sauder School of Business

Professor Matthew Turner, Brown University Keynote SpeechesNext two decades will be very critical for the world "Expressing that he feels honored to receive such a special award previously given to very distinguished scientists like Joseph Nye and organized by Sabancı University which was founded by the great philanthropist Sakıp Sabancı, Professor Lord Stern said: “Climate change has been at the center of my work over the last two decades. Unmanaged climate change poses an immense threat to the future of humanity. On current trajectories, including those embodied in the Paris Agreement of 2015, within a century or so, we are headed for average global temperatures over 3 degrees centigrade above those at the end of the 19th century. With an increase of three degrees probably billions of people would have to move, that would likely result in more profound and severe social conflicts. It would reverse the gains in development we have made over the last half century. To stabilize temperatures, we have to go to zero carbon emissions as a world, and to stay at net zero levels within about 50 years. So, the next two decades will be absolutely critical.” Emphasizing that the drive to net zero can be the most sustainable, inclusive, resilient growth story, Professor Lord Stern said: “This century will be full of discovery, innovation, investment and growth. It will give us cities, where we can move and breathe and be productive. To get there, we will require real leadership, strategy and inspiration. It will also require innovation and creativity, and it will require sound and imaginative finance, surely qualities shown by Sakıp Sabancı in great measure. Turkey is very vulnerable since it is located in southern Europe, but Turkey also has great assets. It has substantial wind and solar resources. And, Turkey, with its special geography and its profound culture, is a focal point for the world. So, we look in this great story for Turkey to be at center stage.” Photo

|

| |

|

Award TopicsFuture Of Multilateralism In Global Turmoil: Rethinking Securiy, Economy, Democracy

In the introduction of his 1993 book titled Out of Control, Global Turmoil on the Eve of the 21st Century, Zbigniew Brzezinski referred to “discontinuity” as “the central reality of our contemporary history.” Rising authoritarianisms in today’s world cast a shadow over what was presumably learned from the atrocities committed by the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century. Global governance through international organizations is shadowed by reliance on unfettered predominance of markets as well as many national obstacles jeopardizing social justice and prospects of peace. International organizations that were formed in the aftermath of the Second World War in order to prevent wars, defend human rights, democracy, and rule of law on an international scale seem to be declining in the course of the past decade. National referandums terminating the ratification of the Constitutional Treaty for Europe as well as Brexit raised questions about the stability and endurance of the European Union. Efforts of the United Nations General Secretariat to resolve conflicts such as the Cyprus issue did not deliver the intended results. Council of Europe’s guidance for democratization especially through the Venice Commission did not find a following among the leaders of its member countries. Leaders and analysts declared the North Atlantic Treaty Organization as obsolete and defunct. Are international organizations really in decline? Is there still room for multilateralism in international politics or is unilateralism becoming the only game in the world? Can international organizations still be engaged in facing global challenges to security, economy, and democracy? What are the new challenges that Turkey is facing in these times of discontinuity and global turmoil? Innovative, original essays on such and related questions are welcome. WinnersWinners of Research Awards:

Cosette D. Creamer from University of Minnesota with "Judicial Responsiveness in the World Trade Organization"

Kerim Can Kavaklı from Bocconi University with "Does the Rise of China Weaken Global Governance? Evidence from the Anti-Trafficking Regime"

Moria Paz from Georgetown University with "A World of Walls". Winner of the Special Jury Award: Joseph S. Nye, Jr. JuryMeltem Müftüler-Baç, Sabancı University – President of the Jury

Ayşe Kadıoğlu, Sabancı University

Fuat Keyman, Sabancı University - Istanbul Policy Center

Kemal Derviş, Brookings Institution – Sabancı University

Erik Jones, Johns Hopkins University

William Burke, Wright University of Pennsylvania Keynote Speeches"Soft power, which is the ability to get what you want through attraction, can come from a country's culture, ideals or policies"

Joseph S. Nye, Jr. spoke: “When we talk about power, we expect others to do what we want them to do. I thought that it was more important to achieve this by making our idea more attractive, by developing a mutual relationship with others. Most of us do this already. So I named it soft power. Soft power is what one needs to make an effective foreign policy. The art of diplomacy is to get agreements. It is underpinned by the idea to sway the preferences of others rather than using force and sanctions to be influential in world politics. Soft power, which is the ability to get what you want through attraction, rather than coercion or payment, can come from a country's culture, ideals or policies."

Nye continued, “I believe that soft power will play a great role in Turkey's future. It is important that Turkey goes back to the soft power approach, and the use of soft power when planning its future. I think that the culture and universities in Turkey will contribute greatly to the country's soft power. Sabancı University and others make great efforts to preserve academic freedom and intellectual integrity. These will add to Turkey's soft power in the future. By utilizing its soft power, Turkey can achieve great things and create tremendous impact. I am confident that the future holds great things for Turkey." Photo

,

|

| |

|

Award TopicsCHALLENGES TO DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE AND LIVING TOGETHER IN TURKEY AND THE WORLD

More than two decades ago, Zbigniew Brzezinski alerted us to a “global turmoil,” steadily stifling the international society’s, and especially the West’s ability to respond to major global challenges. Since then, the West has been in the grip of the multiple crises of globalization, manifested by a myriad of unprecedented and effective security, economic, humanitarian and environmental challenges. While existing democracies have failed to tackle effectively the multiple crises of globalization, a wave of populist movements have begun to shape and frame politics and governance in not only Western democracies, but also in developing countries. These movements, either in government or in opposition, feed on challenges to democracy such as the democratic disconnect between economy and politics, refugee flows and the failures of multiculturalism. Essays providing path-breaking and innovative analyses on these and similar challenges to democratic governance and living together, their causes and impacts, as well as the movements which they foster and the alternative solutions which can be sought are welcome. WinnersWinners of Research Awards:

Selim Erdem Aytaç, Koç University

İpek Çınar, University of Chicago

Berk Esen, Bilkent University

Winner of the Special Jury Award: Adam Przeworski JuryÖzge Kemahlıoğlu, Sabancı University – President of the Jury

Ayşe Kadıoğlu, Sabancı University

Fuat Keyman, Sabancı University - Istanbul Policy Center

John D. Huber, Columbia University

Milan Svolik, Yale University

Dr. Dimitar Bechev, The University of North Carolina

Ellen Lust, Gothenburg University Winning ArticlesThe Appeal of Populism and the Role of Elite Discourse: Evidence from Turkey by Selim Erdem Aytaç,

Koç University

Democracy Dismantled: Strategic Choices of Would-be Autocrats by İpek Çınar, University of Chicago Elective Affinities between Democratic Backsliding and Populism: the Cases of Turkey and Hungary in

Comparative Perspective by Berk Esen, Bilkent University Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. Keynote SpeechesAdam Przeworski: "We share transnational problems which require international efforts to solve. Adam Przeworski said that we shared transnational problems which require international efforts to solve. He noted that the prize was especially relevant to young scientists for continuing their global efforts. Adam Przeworski continued: "All my life, I tried to find answers to two questions. First: How can people divided by values, norms and interests live together? And second: How can democracy coexist with economic and social inequality? Considering that losing parties have a chance to win in the future, political actors and groups will prefer to stay within the system. The balance between economy and democracy is critical. Research suggests that countries which have attained certain levels of economic development were then able to improve their democracies. Democracy is under threat in all countries. For the first time in two hundred years, many parents believe that their children will be worse off than they are. In the longer term, economic consequences will influence the decision of political actors and groups to remain within the boundaries of democracy." Photo

,

|

| |

|

Award Topics"Europeans with Legacies from Turkey in Everyday Life” Labor migration from Turkey to major European capitals began in the 1960s through bilateral agreements. This initial wave of labor migration was soon followed by family reunifications. The migrants and their families who arrived in European cities were initially referred to as "guestworkers" signalling their temporary and foreigner status. A steady increase in the numbers of guestworkers and their families in Europe eventually led to the adoption of a shift from a temporary to a permanent discourse. Such a shift has nowhere been better expressed than in the words of Max Frisch who famously said: “We have summoned a work force, but it is people who are coming” (Man hat Arbeitskräfte gerufen, und es kommen Menschen). By the end of the twentieth century, the more widely used concepts were "Euro-Turks," "Turkish Germans," as well as "Euro-Muslims" who were increasingly second and third generation European borns with legacies from Turkey, fully imbedded and quite effective in their European settings but cognizant of strong family, cultural heritage, and religious ties in Turkey. These population flows have led to the questioning of the convergence between nationality and citizenship which had long been a distinguishing feature of modern politics. It has led to the creation of new lives, interactions, conflicts as well as different modes of coexistence. Daily encounters of cultural and religious differences, while enriching the everyday lives of ordinary people have simultaneously produced conflicts that shaped the contours of the main political cleavages in Europe today. WinnersWinners of Research Awards:

Defne Kadıoğlu Polat, Independent Scholar

Zeynep Selen Artan-Bayhan, City University of New York

Tolga Tezcan, University of Florida Winner of the Special Jury Award: Nermin Abadan Unat JurySenem Aydın Düzgit, Sabancı University – President of the Jury

Ayşe Kadıoğlu, Sabancı University

Fuat Keyman, Sabancı University - Istanbul Policy Center

Riva Kastoryano, CNRS SciencesPo

Lenore G.Martin, Harvard University

Michael Schwarz, Stiftung Mercator Foundation

Thomas Faist, Bielefeld University Winning Articles“At least we have a home here”: Everyday Experiences of Turkish Immigrants in a Gentrifying Berlin Neighborhood by Defne Kadıoğlu Polat, Independent Scholar

“Praying God Abroad: Religious Boundary and the Experiences of Turkish Immigrants in Germany and the United States” by Zeynep Selen Artan-Bayhan, City University of New York

“Building or Burning the Bridges? The Determinants of Return Migration Intentions of German-Turk Generations” by Tolga Tezcan, University of Florida Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. Keynote SpeechesNermin Abadan Unat: Population movements are as old as humanity

Sakıp Sabancı Jury Prize winner Nermin Abadan-Unat began her speech by remarking that population movements were as old as humanity. Abadan-Unat said that the movement of labor in Turkey started at the individual level in the 1950s, and later evolved into mass movements. Discussing Columbia University professor Daniel Lerner's survey of seven Middle Eastern nations titled "The Passing of Traditional Society", drawing attention to the fact that 49% of the Turkish respondents said that, if given no other choice, they would rather die than live somewhere other than Turkey. Nermin Abadan-Unat continued, “60 years after this finding, we have 4.5 million Turkish nationals living across five continents of the world. More than three million of them live in Europe, and 80% of those living in Europe are in Germany." She said that the expansion of transnational areas and developments in communication and technology were the reasons behind this unexpected occurrence. Abadan-Unat added, "We must take a close look at the relationship between countries that sent migrant workers, and those that received them." Photo

,

|

| |

|

Award TopicsNEW CENTERS IN TURKEY: ECONOMY, EDUCATION, ARTS AND PEACE IN CITIES Cities have always been associated with human emancipation. In Europe in the Middle Ages, it was believed that city air brings freedom. Modern cities, too, are defined as areas of high freedom potential for people leaving behind extended family ties and hierarchical agricultural relationships. However, attractive as the potential for human freedom may be, cities are also spheres where economic inequalities, income disparities, cultural differences and ghettoization trends become most visible. Turkey is a country that is going through rapid urbanization. The percentage of the urban population rose from 25% in the 1950s to 75% today. We are now living in an urbanized Turkey with all its risks and potential. Anatolian provinces prove to be the most dynamic ones in terms of rapid urbanization. Processes of change and transformation since the 1980s gave rise to the emergence of new city centers in Anatolia. Cities like Kayseri, Konya, Gaziantep, Eskişehir, Denizli, Çorum and others have become new centers of economic and political power over the last three decades. It is possible to argue that these new city centers pose alternatives to those cities that have been prominent since the early years of the Republic such as Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir. These cities draw attention not only by their recent entrepreneurial ventures, but also their wealth of initiatives in education and artistic activities. What is novel about the emergence and rise of these cities? What are the drivers of entrepreneurship observed in these cities? How compatible are these new urban areas with the fundamental freedoms of citizens? Is the atmosphere (social and political environment) in these cities conducive to liberation – the function that has historically been attributed to cities? How can new urban spaces contribute to development, democratization and peace in Turkey? This topic was chosen for this year's Sakıp Sabancı International Awards in line with the interdisciplinary nature of Sabancı University. Submissions that make general and specic contributions to this subject from a wide and interdisciplinary academic perspective are welcome. WinnersWinners of Research Awards: Azat Zana Gündoğan, Cornell Üniversity and Emrah Şahin, Florida Üniversity Special Jury Award, İlhan Tekeli JurySabancı University Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences member Ayşe Parla: President of the Jury

Ardahan University President Ramazan Korkmaz

Harvard University Faculty Member Neil Brenner

Open University Faculty Member Engin Işın

Sabancı University Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Dean Ayşe Kadıoğlu

Sabancı University Istanbul Policy Center Director Fuat Keyman Winning ArticlesAzat Zana Gündoğan from Cornell University with “Rethinking the Notion of New Centers" Emrah Şahin from the University of Florida with "Dogs and Caravan" Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. Photo

,

|

| |

|

Award TopicsThe topic for the 2015 award was “Living Together, Dialog & Cooperation within Diversity in Turkey”. The tenth Sakıp Sabancı International Research Awards were given at a ceremony held on Friday, April 10th, at Sabancı Center. The ceremony was hosted by Güler Sabancı, Founding Chairman of the Board of Trustees, and President Professor A. Nihat Berker. The winners were Mahiye Seçil Dağtaş from the University of Waterloo with her article ''Beyond Tolerance: Re/Presenting Religious Difference in the Case of the Antakya Choir of Civilizations '', Haydar Darıcı from the University of Michigan with his article “Encounters in the Shadow of War: Turkey’s Kurdish Region '' and Anoush Tamar Suni from the University of California with her article “The Ruin as Archive: Landscape and Memory in Anatolia” WinnersWinners of Research Awards: Mahiye Seçil Dağtaş. University of Waterloo/Beyond Tolerance: Re/Presenting Religious Difference in the Case of the Antakya Choir of Civilizations” Haydar Darıcı. University of Michigan.

“Encounters in the Shadow of War: Turkey’s Kurdish Region” Anoush Tamar Suni. University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

“The Ruin as Archive: Landscape and Memory in Anatolia”. Special Jury Award: Professor Martin Van Bruinessen. University of Utrecht for his publications on prestigious international platforms and his comparative studies on the Turkish case. Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. JuryProfessor Leyla Neyzi: President of the Jury, Sabancı University

Professor Karen Barkey: Columbia University

Professor Ayşe Kadıoğlu: Sabancı University

Professor Fuat Keyman: Sabancı University / İstanbul Policy Center

Emeritus Professor Ronald Grigor Suny: Chicago University

Professor Yael Navaro-Yashin: Cambridge University Winning ArticlesThis year’s theme of the awards was “Living Together, Dialog & Cooperation within Diversity in Turkey” and the winners: Mahiye Seçil Dağtaş. :University of Waterloo. “BEYOND TOLERANCE: RE/PRESENTING RELIGIOUS DIFFERENCE IN THE CASE OF THE ANTAKYA CHOIR OF CIVILIZATIONS”

Please click here for Summary of the Article. Haydar Darıcı. University of Michigan. “Encounters in the Shadow of War: Turkey’s Kurdish Region”

Please click here for Summary of the Article. Anoush Tamar Suni. University of California. “The Ruin as Archive: Landscape and Memory in Anatolia”.

Please click here for Summary of the Article. Keynote SpeechesMartin Van Bruinessen, Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies, University of Utrecht:

“I wish a bright future for young scholars and the society of Turkey”

Jury Award winner Professor Martin Van Bruinessen said, "It will be a great honor if my writings have contributed to living together, cooperation and dialog between ethnic groups in Turkey."

Bruinessen warned academics that their studies may have limited impact on the society. He noted the possible contribution of prominent business figures like Sakıp Sabancı to living together, cooperation and dialog in Turkey.

Professor Martin Van Bruinessen concluded, “The number of young scholars in Turkey is on the rise. The studies of this generation promise hope for Turkey. I am optimistic in my view of the country. I wish a bright future for young scholars and the society of Turkey." Photo

,

|

| |

|

Award TopicsThe topic for the 2014 award was “Gender Equality in Turkey”. The ninth Sakıp Sabancı International Research Awards were given at a ceremony held on Tuesday, May 13th, at Sabancı University Sakıp Sabancı Museum - the Seed. The ceremony was hosted by Güler Sabancı, Founding Chairman of the Board of Trustees, and President Professor A. Nihat Berker. The winners were Akanksha Misra with her article ''Beyond Numbers: Rethinking the Education and Empowerment of Girls in Turkey'', Aslı Zengin with her article “Questioning Calculations of Justice: Criminal Law, Hate Crimes and Queer Approaches '' and Emine Gökçen Yüksel (Universität der Bundeswehr Munich), Stephan Stetter (Universität der Bundeswehr Munich) and Jochen Walter (Universität Bielefeld) with their article “Properties of Modern Women and the Negotiation of Gender Norms within Space” WinnersAkanksha Misra. University of Washington/Gender, Women and Sexuality Studies.

“Beyond Numbers: Rethinking Girls’ Education, Empowerment, and Gender Equality in Turkey” Aslı Zengin. University of Toronto, Department of Anthropology, Women and Gender Studies Institute.

“Contesting Calculations of Justice: The Criminal Law, Hate Crimes and Queer Lives” Emine Gökçen Yüksel. Universität der Bundeswehr Munich.

Stephan Stetter. Universität der Bundeswehr Munich.

Jochen Walter. Universität Bielefeld.

“Modern Female Subjectivities and the Spatial Negotiation of Gender Norms”. Special Jury Award: Deniz Kandiyoti. University of London for her publications on prestigious international platforms and her comparative studies on the Turkish case. Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. JuryProfessor Sibel Irzık: Sabancı University / Gender and Women’s Studies Forum

Professor Isabelle de Courtivron: Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Professor Cemal Kafadar: Harvard University

Professor Ayşe Kadıoğlu: Sabancı University

Professor Fuat Keyman: Sabancı University / İstanbul Policy Center Winning ArticlesThis year’s theme of the awards was “Gender Equality in Turkey” and the winners: Akanksha Misra. :University of Washington. “Beyond Numbers: Rethinking Girls’ Education, Empowerment, and Gender Equality in Turkey”

Please click here for Summary of the Article. Aslı Zengin. University of Toronto. “CONTESTING CALCULATIONS OF JUSTICE: THE CRIMINAL LAW, HATE CRIMES AND QUEER LIVES”

Please click here for Summary of the Article. Emine Gökçen Yüksel. Universität der Bundeswehr Munich. Stephan Stetter. Universität der Bundeswehr Munich. Jochen Walter. Universität Bielefeld. “Modern Female Subjectivities and the Spatial Negotiation of Gender Norms”.

Please click here for Summary of the Article. Keynote SpeechesDeniz Kandiyoti, Department of Development Studies, University of London:

“The patriarchal is a crumbling structure that has difficulties in re-producing itself.” Deniz Kandiyoti, this year’s winner of the Jury Prize, said that at one point in history, slave trade was widespread and scientific theories, religious and creationist rationale were used to legitimize this practice. Kandiyoti remarked that people were still being traded today, although most of them were women and children, and similar scientific, religious and creationist arguments were still being used to make the issue seem legitimate. Saying that she viewed gender issues like a puzzle that needs solving, Kandiyoti argued that under the 21st century conditions, the patriarchal is a crumbling structure that has difficulties in re-producing itself. Deniz Kandiyoti concluded, “The patriarchal is being resurrected as an administrative science. But the new generation rises up against subservience and obedience. The new generation will lead us to emancipation.” Photo

,

,

|

| |

|

Award TopicsThe topic for the 2013 award was “Checks and Balances in a Democracy: Turkey in a Comparative Perspective”. The seventh Sakıp Sabancı International Research Awards were given at a ceremony held on Wednesday, June 26th, at Sabancı University Sakıp Sabancı Museum - the Seed. The ceremony was hosted by Güler Sabancı, Chairman of the Board of Trustees, and President Professor A. Nihat Berker. The winners were Meral Uğur Çınar & Kürşad Çınar with their article '' Building Democracy to Last: the Turkish Experience in Comparative Perspective'', Yunus Sözen with his article ''Paradoxes of Liberal Constitutional Democracy and the Populist Challenge'' and Ioannis Grigoriadis wit his article ''Democratic Transition and the Rising Tide of Majoritarianism: Comparing the Cases of Greece and Turkey''. WinnersWinners of Research Awards: Meral Uğur Çınar. The New School Department of Political Science and Sociology in New York, USA.

Kürşat Çınar. Ohio State University, Doctorate in Politics in Columbus, USA.

“Building Democracy to Last: The Turkish Experience in Comparative Perspective” Ioannis N. Grigoriadis. Bilkent University Political Science and Public Administration Department in Ankara, Turkey. “Democratic Transition and the Rising Tide of Majoritarianism: Comparing the Cases of Greece and Turkey” Yunus Sözen. Özyeğin University International Relations Department in İstanbul, Turkey. “Paradoxes of Liberal Constitutional Democracy and Populist Challenge”. Special Jury Award: Ergun Özbudun of the Istanbul Şehir University Law School for his publications on prestigious international platforms and his comparative studies on the Turkish case. JuryProfessor Ayşe Kadıoğlu: Sabancı University

Professor Fuat Keyman: Sabancı University / İstanbul Politikalar Merkezi Direktörü

Assistant Professor Aslı Bali: University of California Los Angeles

Professor Çağlar Keyder: State University of New York ve Boğaziçi University

Emeritus Professor Deniz Kandiyoti: University of London

Elaine Papoulias: Harvard University

Professor Jenny White: Boston University Winning ArticlesThis year’s theme of the awards was “Checks and Balances in a Democracy: Turkey in a Comparative Perspective” and the winners: Meral Uğur Çınar. The New School Department of Political Science and Sociology in New York, USA. Kürşat Çınar. Ohio State University, Doctorate in Politics in Columbus, USA. “Building Democracy to Last: The Turkish Experience in Comparative Perspective” Ioannis N. Grigoriadis. Bilkent University Political Science and Public Administration Department in Ankara, Turkey. “Democratic Transition and the Rising Tide of Majoritarianism: Comparing the Cases of Greece and Turkey” Yunus Sözen. Özyeğin University International Relations Department in İstanbul, Turkey. “Paradoxes of Liberal Constitutional Democracy and Populist Challenge”. Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. Keynote SpeechesErgun Özbudun, Faculty of Law, Istanbul Şehir University:

“Democracy is a regime of checks and balances”

Professor Ergun Özbudun, winner of the Special Jury Award, began by saying that the award was one of the proudest achievements of his long career. Ergun Özbudun said, “Checks and balances is a very wise choice as the theme this year considering the current situation in Turkey. Democracy is a regime of checks and balances. The motive behind the constitutional movement is to limit the power of the government and protect the rights of the individual. Separation of powers is essential in achieving this, and the system of checks and balances has been devised and developed as a vital part of all democratic regimes. It is not possible to conceive a democracy without checks and balances.”

“The higher democratic standards are in a country, the better will be the quality and international recognition of work in this area.”

Ergun Özbudun said, “Looking back 50 years, I see that Turkey has gained great distance both in quality and quantity. In the early 1960s, the number of professors and researchers in either social science or political science could be counted on two hands. Today, there are hundreds of scholars in both disciplines, and the increase is not limited to numbers.The studies of Turkish researchers, political scientists and social scientists receive increasing recognition and coverage in international publications. It must be kept in mind that sciences in general, social sciences in particular, and specifically subjects like constitutional law and Turkish politics are closely tied to the level of freedom of thought and the quality of democracy in the country. The higher democratic standards are in a country, the better will be the quality and international recognition of work in this area.” Photo

,

,

|

| |

|

Award TopicsThe topic for the 2011 award was "New Directions for Turkish Foreign Policy in a Changing World Order: Challenges and Opportunities". The sixth Sakıp Sabancı International Research Awards were given at a ceremony held on Monday, June 6th, at Sabancı University Sakıp Sabancı Museum - the Seed. The ceremony was hosted by Güler Sabancı, Chairman of the Board of Trustees, and PresidentProfessor A. Nihat Berker. The winner was Professor Kemal Kirişci from Boğaziçi University. WinnersThe first prize: Kemal Kirişci. Boğaziçi University. “Turkey’s engagement with its neighborhood: A “synthetic” and multi-dimensional look at Turkey’s foreign policy transformation” .

Second prize: Güneş Murat Tezcur & Alexandru Grigorescu. Loyola University Chicago. “Europeanization Regionalism in Turkish Foreign Policy” .

Third prize: Clemens Hoffman & Can Cemgil. Sussex University “A Pax Turca in the Middle East?” . JuryProf. Dr. Sabri Sayarı: Sabancı University

Prof. Dr. Ustun Erguder : Director, Istanbul Policy Center / Sabancı University

Prof. Dr. Mustafa Aydın: Kadir Has University

Prof. Dr. Riva Kastoryano: Center for International Studies and Research Director, Paris

Associate. Prof. Martin Sampson: Minnesota University

Prof. Dr. Malik Mufti: Tufts University

Dr. Nathalie Tocci: Instituto Affari Internazionali’de Senior Fellow Winning ArticlesProf. Dr. Kemal Kirişci / “Turkey’s engagement with its neighborhood: A “synthetic” and multi-dimensional look at Turkey’s foreign policy transformation” Doç. Dr. Güneş Murat Tezcur & Doç. Dr. Alexandru Grigorescu / “Europeanization Regionalism in Turkish Foreign Policy” Dr. Clemens Hoffman & Can Cemgil / “A Pax Turca in the Middle East?” Dr. Ioannis N. Grigoriadis / "Turkey’s New Foreign Policy Activism: Evaluating its Political and Economic Underpinnings” Dr. Alper Kaliber / “Reorganization of Geopolitics: Understanding the New Activism in Turkish Foreign Policy” Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. Keynote SpeechesMartin Sampson Notes for speech on behalf of the jury at the 2011 Sakip Sabanci Award ceremony at the Sabanci Museum on June 8, 2011 Winner: Kemal Kirişci Just as it is appropriate and advantageous that Turkey has an ambitious, nuanced, and complex relationship with the outside world, it is advantageous and important that scholarship that seeks to understand these nuances and complexities flourish. That is the purpose of the Sakip Sabanci award, and the diversity and number of papers it has attracted attest to the richness of the subject. There was a time decades ago when a significant part, although not all, of Turkey’s foreign policy was derivative of someone else’s cold war. Two decades ago a time ensued in which many wondered if the end of the cold war meant a strategic marginalization of Turkey that would significantly reduce its importance internationally. Few if any people in that era could have imagined that two decades later Turkey would have significant latitude to find its own way in a number of internationally crucial foreign policy arenas. Few people in that era could have imagined how the topic of Turkish foreign policy would widen from a focus on state activities to a continuation of that focus plus a consideration of impacts various societal and economic groups would play in Turkey’s relationship with the outside world and its foreign policy. The current era is a time in which scholarship has become far more important for understanding and for democratic debate because of these kinds of changes. The existence of this award could not have found a better era, in regard either to the fascination of the topic or the importance of informed debate and discussion. I salute those who created this award. The papers submitted this year present an array of terms which underscore the interest of their authors in the orientation and/or the complexity of Turkey’s relationship with the outside world. “Concurrent repositioning”, “omni-enmeshment”, “neo-Ottoman”, “Pax Turca,” “new foreign policy activisim” are some of them, underscoring the debate on how best to understand the complexities of Turkey’s foreign policy. Some of the papers examined the implications of Turkey’s leverage as that relates to its foreign policy endeavors. There were case studies on narrow but crucial aspects of Turkey’s foreign policy some of which examined how well the policy was implemented in those particular circumstances. There were case studies on highly visible, broader parts of Turkey’s policy. And there was one paper that argued the advantages of an ambiguous foreign policy in a turbulent region. One of the central challenges is to understand the new context in which Turkey is operating. Part of that context is driven by outside factors, such as the overthrow of a Mubarak or the revolt in Syria against the Asad regime. Part of the context, however, is the rise of Turkey’s international presence as a result of Turkey’s own efforts of many kinds. It is not difficult to find evidence. Examples of such evidence include the trivial point that there is Turkish chocolate for sale at the Timbucktu airport or that a finalist and in the eyes of many the best entry in New York City’s contest for a new taxicab came from a Turkish company to the fact that it was Turkey whose embassy in Tripoli was able to mediate the release of reporters despite Turkey’s complex situation of NATO membership plus extensive economic interests in Libya. The evidence is abundant. The difficulties are to understand the major kinds of this evidence, how they add up, and what kinds of implications that has for Turkey’s foreign policy. These are not easy tasks, which is precisely why academics and others who analyze Turkey’s international situation are so valuable and why it is so helpful to have an award that helps stimulate and recognize their scholarship. Photo

,

|

| |

|

Award TopicsThe topic for the 2010 award was "Multiculturalism in the Governance of the European Union and Turkish Accession". Participants studied the issues and challenges that multiculturalism presents for the governance of the European Union. In particular, the authors assessed the benefits and contributions of Turkey’s accession to the EU’s governance in meeting these challenges. The fifth Sakıp Sabancı International Research Awards were given at a ceremony held on Tuesday, June 8th, at Sabancı University Sakıp Sabancı Museum - the Seed. The ceremony was hosted by Güler Sabancı, Chairman of the Board of Trustees, and President Professor A. Nihat Berker. The winner of the first prize was Juliette Tolay from University of Delaware. WinnersThe first prize: Juliette Tolay, University of Delaware, with her essay titled: "Turkey’s Other Multicultural Debate: Lessons for the EU". Second prize: Dr. Akça Ataç, Çankaya University, with her work titled "Another Brick on The Tower of Babel: Turkey's Possible Challenges and Contributions to The EU’s Language Policy". Third prize: Yrd. Doç. Dr. Şener Aktürk; Visiting Lecturer, Department of Government, Harvard University; Assistant Professor, Department of International Relations, Koç University, with his work titled "The Impact of Ethno-Religious Demography on Strengthening Secularism and the

Dynamics of Multiculturalism: Turkey’s Accession into the European Union". JuryProf. Dr. Sabri Sayarı: Sabancı University

Joost Lagendijk: Sabancı University

Prof. Dr. Ziya Öniş: Koç University

Dr. Philip Robins: St Antony's College

Prof. Dr. Uffe Ostergaard: Copenhagen Business School

Prof. Dr. Raoul Motika: Universität Hamburg Winning ArticlesJuliette Tolay / Turkey's Other Multicultural Debate: Lessons for the EU Akça Ataç / Another Brick on the Tower of Babel: Turkey's Possible Challenges and Contributions to the EU's Language Policy Şener Aktürk / The Impact of Ethno-Religious Demography on Strengthening Secularism and the Dynamics of Multiculturalism: Turkey's Accession into the European Union Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. Keynote SpeechesJoost Lagendijk Notes for speech on behalf of the jury at the 2010 Sakip Sabanci Award ceremony at the Sabanci Museum on June 8, 2010 Winner: Juliette Tolay Doctoral candidate at the University of Delaware, USA Title of essay: Turkey’s Other Multicultural Debate: Lessons for the EU Most of the time in relation between Turkey and EU: Turkey has to adapt to European standards

At two levels: bringing legislation in line with EU acquis (negotiating about chapters) and political reforms necessary to fulfill Copenhagen criteria

One way street: EU asks/demands, Turkey has to change laws/mentality. Therefore the word ‘negotiations’ is totally wrong.

Also on migration: Turkey has to deliver: sign a re-admission agreement (accept returned migrants from Europe), introduce biometrical passports, guard the borders better. EU will assist Turkey the coming years with hundreds of millions euro’s to try and reach these goals. Then, maybe, EU countries will soften their visa policy.

On multiculturalism: EU often lectures Turkey on the lack of rights for ethnic and religious minorities. Situation in EU member states very different + all have problems with dealing with new migrants. Still, again one way street.

That makes this essay so refreshing: two way street approach

It looks at the way Turkey, Turkish society, deals with migrants. Not only the ‘traditional’ ones with Turkic background but also the new ones from Africa and Asia. In a way restoring the multicultural character of the Ottoman Empire that was lost during the Turkish republic.

Have to be careful there with the numbers. In Turkey we are speaking of relatively small numbers, not to be compared with the situation in the Ottoman Empire in the past and the present numbers of migrants in EU member states.

Still, very interestingly, the author looks at the way these new migrants are being seen and treated in Turkey:

Main characteristics:

Few limitations on getting into the country

No official policy on integration

Flexibility in society in accommodating the newcomers

No ‘unhealthy’ debate on multiculturalism

In EU: exactly the opposite

Can EU learn something from Turkey? Again, be careful because magnitude of problems and history of migration politics are totally different.

Still: provocative proposal for the EU to look more carefully at Turkey’s (lack of) migration policy. Is more in line with ‘the nature of the globalized world that is encouraging new forms of mobility’. Maybe the EU should accept migration and multiculturalism as facts of life that can better be handled in a flexible way than try to regulate each and every movement in detail.

It makes you think. It makes you smile. It makes you wonder.

And that makes it a good essay that deserves to win this price. Photo

,

|

| |

|

Award TopicsThe topic for the 2009 award competition was “Pluralism in Contemporary Turkish Society and Politics”. The fourth Sakıp Sabancı International Research Awardswere given at a ceremony held on Tuesday, May 26th, at Sabancı University Sakıp Sabancı Museum - the Seed. The ceremony was hosted by Güler Sabancı, Chairman of the Board of Trustees, and President Professor Tosun Terzioğlu. The winner of the first prize was the young researcher from the University of Vermont, Kabir Tambar. WinnersThe first prize: Dr. Kabir Tambar of University of Vermont, with his essay titled: "Paradoxes of Pluralism: Ritual Aesthetics and the Alevi Revival in Turkey". Second prize: Nora Fisher Onar, doctoral candidate at the University of Oxford with her work titled "Beyond Binaries: 'Europe', Pluralism, and a Revisionist-Status Quo Key to Turkish Politics". Third prize: Murat Somer, Associate Professor of Koç University with his work titled "Democracy (For Me): Religious and Secular Beliefs and Social and Political Pluralism in Turkey". JuryProfessor Sabri Sayarı: Sabancı University Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

Professor John Waterbury: Former President of the American University of Beirut Faculty of Political Sciences, Lebanon; Emeritus Professor of Political Sciences, Princeton University

Professor Nilüfer Göle: Director, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Centre d'Analyse et d'Intervention Sociologiques, France

Professor Fuat Keyman: Koç University, Professor of International Relations

Professor David Shankland: University of Bristol, Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, UK

Professor Kalypso Nicolaidis: University of Oxford, Professor of International Relations Winning ArticlesKabir Tambar / Paradoxes of Pluralism: Ritual Aesthetics and the Alevi Revival in Turkey Nora Fisher Onar / Beyond Binaries: 'Europe', Pluralism, and a Revisionist-Status Quo Key to Turkish Politics Murat Somer / Democracy (For Me): Religious And Secular Beliefs And Social And Political Pluralism In Turkey Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author. Keynote SpeechesJohn Waterbury Keynote Speech by John Waterbury, Princeton University Transcript Good evening ladies and gentlemen. It is a great honor for me to be here and to have been a member of the jury for this year's award ceremony. It is an even greater honor for me to be here before you this evening. I greatly appreciate the privilege and I salute Sabancı University and the Sabancı family for sponsoring this contest- this year devoted to pluralism in Turkish society. I apologize to you all that I am not able to deliver my remarks in Turkish. But I must say that the essays that I read were all written in English and in English better than my own.

Indeed those eight essays that we the jury considered were all of very high quality. I learned from them all and I appreciate the opportunity to read them all. I want to make a few summary remarks about those essays- at least my personal impressions of them. And then a few general remarks about pluralism itself. I should warn you that I am not- I do not consider myself a student or an expert on pluralism. I speak more as someone who simply lives in society whether it is in the US or here in the Middle East. And one who worries about diversity, pluralism and the respect for a wide range of opinions and practices.

The essays, with the exception of one, I think I can say fairly, did not spend a lot of time on what we would call the theory of pluralism. Only one seemed to engage that topic in some detail. Rather the essays plunged into what I would call into the mechanics of pluralism. That is how in Turkish society do various groups that may not share in the dominant ideology and paradigm of the country try to find their place, try to gain legitimacy and respect and indeed try to gain legal status in the system. So the essays moved rather quickly from the question of what is pluralism and why it is important and how in a theoretic way do we try to protect it to the actual mechanics: What our different groups are doing to try to carve out a place for themselves in Turkish society and Turkish politics. And they addressed what I think would probably the authors more pressing concerns in academic terms. Some were looking at an issue that is called social movements and how social movements form and establish themselves. Some were interested and using a methodology of either survey research that is public opinion or opinion research and content analysis of newspapers. Some employed an anthropological approach to try look right at the grassroots level. And indeed the winner of the contest was looking at the grassroots level from an anthropological, sociological point of view of how a group in current temporary Turkey seeks to carve and nurture itself. And at least one of the essays was very concerned with general political attitudes of the Turkish political elite. So very diverse approaches to this issue. But as I say it seems to me the common thread was looking at the mechanics rather than the general theory of pluralism in contemporary Turkish society and Turkish politics.

What struck me in reading across these papers was the sensitivity of the authors to certain paradoxes, certain contradictions that are merged in this study of mechanics and I'll just mention three or maybe four. One for instance, indeed I think the winner, I hope I don't abuse his own really profound analysis, looked at a paradox of the Alevis. Asserting their dead identity through a performance which is characterized as folkloric and using- and that was acceptable in a folkloric sense acceptable to present to a non-Alevi public. But in so doing, in a way, the Alevis debased their own religious identity which was the very thing they sought recognition for. So it was kind of a paradox in the sense that they had to go through a public folkloric presentation in order to gain official recognition of their religious identity. But in so doing they in a way debased that religious identity. There is the paradox mentioned in some papers of secularist Turks who feared the pressure coming from Europe to keep the military totally out of politics and in so doing perhaps jeopardizing what they, the secularists saw, as the last defense of their secularism. They were caught between two pressures and in a way have not yet reconciled that contradiction. A third that I noticed in at least two or three of the papers was in fact the role of the AKP which I think fascinated many of the authors where what does this represent. Presented as a challenge to what we might call the Kemalist paradigm prevailing in Turkey since the founding of the republic but at the same time perhaps borrowing one of the tenets of the Kemalist paradigm which either explicitly or implicitly has been that Sunni Islam is the religion of state. So AKP sets itself up as the alternative to the Kemalist paradigm but yet maybe borrows one of the basic pillars of it. So I am gonna conclude my remarks on those papers just saying that mechanics of pluralism are not clear cut in Turkey, the agendas of different groups are not consistent at all times. There are contradictions and paradoxes that either a student of this phenomenon or a practitioner must appreciate or I think take some delight in.

Let me move to some more general remarks on pluralism itself and I again emphasize that I am not an expert or a student. So I ask these simply as an observer. And, the first that, the first generalization that I would make is that at least in Western political theory, the concern for pluralism and the protection of pluralism, I believe arises out of a much deeper concern with what we might call the tyranny of the majority in democracies and this comes out of ancient democratic theory- a fear that majorities, even though they practice in a democratic system, may impose short term solutions that are highly destructive to society. In other words, there is an ancient and deep mistrust of the majority even if it expresses its voice in a democratic way. And therefore there must be constitutional, institutional protections for minorities. I think there are so many examples in history that show the stupidity of the majorities, the viciousness of majorities. We do not need to dwell on this terribly long but I just would say two examples familiar I think to most of you. Adolf Hitler was the product of a democratic process. There can be circumstances in which popular passions are aroused and brought to a point where they do extraordinary harm. Perhaps on a lesser scale but one of the most shameful periods in my own country's history, the US, again came under a period of very high stress, Pearl Harbour and the beginning of the World War II at least for the US where the US interned virtually every Japanese citizen, every US citizen of Japanese origin during the duration of the war. We learned later that we needed to have constitutional protections for that, for any minority so that even though with the popular will of the majority of Americans at the time, we needed to have that, the Japanese, at least the Japanese in the US did not have those protections. So I think one of our concerns that lead to our concern with pluralism and pluralist systems, is that the majority can and under stress often does make terrible mistakes.

Diversity and pluralism has been regarded more often as a threat to society than as a blessing and a source of strength. It is seen as a way to tear apart the fabric of a nation, or an empire or some kind of political unit. It is seen as the way that the enemy can enter your society and exploit the differences to their advantage. Therefore, it is often the case that political systems try to contain or suppress pluralism. And that again from one of a political, liberal persuasion, is abhorred and repulsive but it's simply been the general modus vivendi in most societies in the world. But it has been, I think prevalent for understandable reasons, in post-colonial society in the developing countries- those countries that have been subjected to foreign rule. I myself have been a student of the Arab world, of North Africa, and the Arab countries and throughout, scholars from those countries would say that friends, Britain and then in the later phase the US, has exploited our differences they created a kind of artificial sense of identity among different peoples, ethnic groups, religions in our societies in order to divide and rule, divide and conquer, maintain their colonial control. And therefore in order to build our nations as the way they should be, we cannot tolerate these differences. We must- we must build new identities that overcome these old identities.

And so I would say since the World War II, in many societies, those that are from minorities- they may be ethnic minorities, they may be religious minorities, they may hold different political views- they have been regarded as not only as dangerous but as, in some sense, traitors. As agents of powers, external powers, that want to dominate the local society. So it is an uphill battle to develop pluralist systems. And I take it as a great sign of encouragement that here in Turkey and here at Sabanci University, there seems to be a strong will to explore pluralist systems, understand how they function and how they can be an element of strength rather than perceived as an element of weakness. Thank you again for allowing me this opportunity to address you. It has been a great honour and good evening to you all. Photo

,

|

| |

|

Award TopicsIn 2008, the topic of the competition was "The Ottoman Legacy for Contemporary Turkish Culture, Institutions, and Values". Participants studied the reflections of the Ottoman heritage on the culture, institutions and values of contemporary Turkey. The first prize went to Amy Singer, professor of Ottoman History in the Department of Middle Eastern and African History at Tel Aviv University, with her essay, "The Persistence of Philanthropy". WinnersFirst Prize: Amy Singer, aAsst. Prof. of Ottoman History in the Department of Middle Eastern and African History at Tel Aviv University, with her essay, "The Persistence of Philanthropy". Second Prize: Maureen Jackson, doctoral candidate at the Washington University Comparative Literature Department, with her essay "Crossing Musical Worlds: Jews Making Ottoman and Turkish Classical Music". Third Prize: Olivier Bouquet, Asst. Prof. at the Nice Sophia-Antipolis University, and research fellow at the Modern and Contemporary Mediterranean Centre in Nice, with his essay "Old Elites in a New Republic: The Reconversion of Ottoman Bureaucratic Families in Turkey (1909-1939)". Honorable mentions: Zoe Griffith, CASA fellow at the American University in Cairo, with her essay "Calligraphy and the art of statecraft in the late Ottoman Empire and modern Turkish Republic" and

Denise R. Gill, doctoral candidate at the University of California, Santa Barbara's Ethnomusicology and Women's Studies Department with her essay "Performing Mesk, (re)Articulating History: Legacies of Transmission in Contemporary Turkish Musical Practices". JuryProf. Dr. Sabri Sayari: Professor at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Sabancı University.

Prof. Dr. Resat Kasaba: Professor at the University of Washington, The Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies.

Prof. Dr. Sukru Hanioglu: Professor at University of Washington, The Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies.

Prof. Dr. Fikret Adanir: Professor at Sabancı University, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences.

Prof. Dr. Sevket Pamuk: Professor at Bogazici University.

Prof. Dr. Jacob Landau: Professor at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Department of Political Science.

Dr. Caroline Finkel: Author.

Prof. Dr. Jenny White: Professor at Boston University, Department of Anthropology. Winning ArticlesAmy Singer

Department of Middle Eastern & African History

Tel Aviv University

First Prize - 2008 Competition

The Ottoman Legacy for Contemporary Turkish Culture, Institutions and Values The Persistence of Philanthropy

One of the most profound Ottoman legacies to contemporary Turkey is the central role of private philanthropy as a vehicle for shaping culture and society. Two principle legacies of Ottoman philanthropy exist in Turkey today. The first is cultural, apparent in the thriving practice of elite philanthropy; the second is physical, readily discovered in the urban fabric of most Turkish cities. It is the Ottoman philanthropic tradition and its impact on Turkey that claim our attention in the present study, particularly with respect to the city of Istanbul. Both continuities and changes are apparent from imperial to republican times: in the identity of the donors, the sources and locus of wealth, the importance of foundations, the motivations for giving, the choice of projects, the physical impact of donations, and the identity of the beneficiaries.

Yet today's dynamic culture of private charitable giving in Turkey is not solely the result of inherited Ottoman ideology and practices, just as Ottoman philanthropic practices were themselves the result of combined Muslim, Turco-Mongol, Byzantine, and Arab influences. For Turkey, the example of philanthropy in some European countries and the United States also had an impact beginning in the nineteenth century. Since 1923, however, the specific Turkish experience has transformed philanthropy in Turkey into practices that are at the same time identifiably local and emphatically global.

Gift giving, a universal of human societies, is the larger sociological framework within which the study of philanthropy offers insights for understanding human history more generally. According to sociologist Marcel Mauss, it is the continuous exchange of gifts between individuals that creates social order and stability, and charitable giving is a special case of gift exchanges. An investigation of philanthropy in any society reveals much about its organization, the loci of wealth and power, and the distribution of responsibility for social welfare and public services.

The evidence of large-scale elite philanthropy can hardly be missed in the Turkish landscape today, whether the projects are historical or contemporary. Some further aspects of this philanthropy endure, such as a common sense of elite obligation, the participation of men and women, and the engagement of philanthropy in the competition for status and influence. Today, the economic elite has replaced the sultans and pashas as premier benefactors, with personal or corporate donations even rivaling government sources of assistance.

The motivations for contemporary philanthropy echo the Muslim consciousness of Ottoman donors, although philanthropy no longer functions to ensure the political legitimacy of the ruling house. It does, however, serve to legitimize wealth, and notably so in the context of the early Turkish republic where profit-making was not necessarily well-regarded. Yet several Turkish donors specifically characterize their donations as using their wealth for the well-being of society, giving back to the society that made them wealthy. Philanthropy remains the means to contribute to a wider community, whether it is the community of Turkish citizens, of Muslims or another confessional group, of a town, a neighborhood, or a profession.

While the wealth of Turkey's philanthropists derives from sources rather different from those of their Ottoman predecessors, their projects reflect partial continuity. The focus remains on institutions of social welfare, like education and health. However, the contemporary vision of the purpose of education and health care is often of capacity building and social justice rather than only the preservation of a religious or legal tradition. Scholarships, dormitories, primary schools, and universities are designed according to a conscious program of social engagement alongside a curriculum intended to make Turkey and Turkish students competitive in science, technology and the arts. Education is a tool of individual empowerment and community formation, as well as of national economic development. At the same time, the creation of museums and the funding for performing arts - such as that provided by the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and the Arts established by the Eczacıbaşı Foundation - signify changing visions of what is good and beneficial for society. As in Ottoman times, the beneficiaries are not limited to the materially poor and needy. Rather, private elite philanthropy contributes to many segments of society and in this reflects the manifold motivations for giving.

Please do not cite or reproduce without permission of the author.

© Amy Singer, 2008 Maureen Jackson

Washington University

Comparative Literature Department

Second Prize - 2008 Competiton

Crossing Musical Worlds: Jews Making Ottoman and Turkish Classical Music This paper investigates the multiethnic art world enabling Turkish Jewish religious music to parallel broader musical practices in the Ottoman empire and Turkey. It seeks to explain why Hebrew classical music continues to be performed in Istanbul, given the diminished size of the Jewish community in Turkey today. While research has been conducted on the musicological relationships between Hebrew religious music and Ottoman classical forms, scholars have paid less detailed attention to how, on a socio-historical level, such confluences developed. Focusing primarily on the Maftirim repertoire (Hebrew religious compositions that closely parallel Ottoman classical suite forms), this study is part of a larger dissertation project encompassing the late Ottoman and Republican eras as dynamic periods of musical and social change. Through several biographies of late Ottoman/early Republican Jewish composers in the framework of an "art world," it is possible to conceptualize a classical music world in Jewish and non-Jewish musicians met regularly in relatively inclusive spaces in the city, thus developing a common classical music practice across religious lines. The Mevlevi lodge and palace represented important spaces, owing to their centrality to classical music education, with longterm historical evidence of musical interchange between lodge and synagogue, and invitations for Jewish composers to teach or perform at the palace. Later, at the turn of the 20th century other musical venues developed, such as music stores and schools, as well as recording studios, where diverse musicians would meet. Specifically, it was Jewish composers who also held positions of authority in the synagogue (chief rabbi, head of a single congregation or prayer leader) who served as primary cultural carriers of classical music between synagogue and broader musical culture, owing to their status to circulate among certain places and people, and their role in transmitting the music in the synagogue.